Malaysia has seen a significant surge in EV adoption over the past year, largely driven by tax exemptions for fully imported electric vehicles.

According to the Road Transport Department (JPJ), a total of 44,813 EVs were registered in Malaysia in 2025, representing more than 100 percent year-on-year growth compared to 21,789 EVs in 2024. In December 2025 alone, 8,123 EVs were registered, more than triple the number recorded in the same month in the previous year.

This momentum, however, comes at a critical inflection point. The tax holiday for fully imported EVs has ended on 31st December 2025, yet many fundamental questions remain unanswered if Malaysia is serious about sustaining EV adoption and achieving its stated goal of 15% of total industry volume by 2030.

Several weeks into the new year, full details of the post-holiday tax structure for imported EVs have yet to be officially announced by the government, leaving consumers and automakers waiting for clarity.

Malaysia needs long term clarity on EV policy

Malaysia’s biggest weakness today is not a lack of incentives, but a lack of long term certainty. Import duty, excise and SST exemptions all come with expiry dates. Extensions tend to be announced late, and local assembly (CKD) incentives are currently short term as they are in place until the end of 2027.

For automakers, it complicates pricing, localisation and investment planning. For charge point operators (CPO), unclear EV sales trajectories make it difficult to commit to new charging sites and capacity upgrades, both of which depend on predictable growth in EV adoption.

As of the end of 2025, Malaysia’s EV adoption currently stands at about 5% of total industry volume, lagging behind regional peers such as Indonesia at around 15%, Thailand at 20%, and Singapore, where EVs now make up over 40% of new registrations.

Thailand and Indonesia have taken a more structured approach to EV incentives by tying support to longer term industrial objectives rather than short term sales stimulation.

In Thailand, incentives are structured through programmes such as the BEV 3.5 policy, which runs from 2024 to 2027. It combines tax reductions, purchase rebates and import duty relief with requirements that brands commit to local assembly and production commitments, which drives long term investment toward domestic EV manufacturing.

In Indonesia, EV incentives are tied to Domestic Component Level (TKDN) requirements under the PPN DTP scheme, where VAT relief is linked directly to local content thresholds and incentives for fully imported EVs are gradually being reduced as policy shifts toward local assembly.

The policy structure has already pushed several automakers to establish or expand local EV assembly operations in Indonesia, including Hyundai, Toyota, Wuling, DFSK and VinFast.

Right to charge and EV Charger as a utility

One of the key benefits of owning an EV is the ability to enjoy convenient and affordable charging at home. As shared by Tesla Malaysia, around 80% of its EV owners have access to a home charger.

However, Malaysians living in stratified properties such as apartments and condominiums face a very different reality. Many encounter unclear approval processes, concerns over liability from management bodies, and uncertainty around electrical capacity when attempting to install EV chargers.

This is where the absence of a clear Right to Charge becomes a structural barrier to EV adoption. In more mature EV markets, Right to Charge policies give residents the legal right to install a private EV charger at their designated parking bay, subject to defined technical and safety requirements. Building management bodies are not required to pay for the installation, but they also cannot block EV charger installations, as long as it complies with the required safety and technical standards.

Where individual chargers are not feasible, residents should, at the very least, have access to shared charging facilities within the development. Whichever approach is adopted, the objective is the same: to ensure EV owners have convenient and affordable access to charging at home.

For new developments, both residential and commercial, EV charging infrastructure must be treated as a basic utility, similar to electricity, water and internet access. With Malaysia targeting EVs to account for 80% of total industry volume by 2050 under the Low Carbon Mobility Blueprint and the National Energy Transition Roadmap, a clear mandate is needed to define the minimum number of charge points and power capacity requirements for all new buildings.

If few people would buy a home today without fibre broadband access, who would choose a property without EV charging facilities in the future? Clear EV-ready building standards and utility-led mandates are no longer nice to have. They are necessary foundation to make EV ownership practical for all Malaysians.

Looking at our neighbour down south, Singapore has set a target to have EV chargers at all Housing & Development Board (HDB) towns by the end of 2025. It is reported that 90% HDB car parks are already equipped with chargers, with utilisation now at around 18%.

Malaysia only has one-fifth of the EV charging points of Singapore

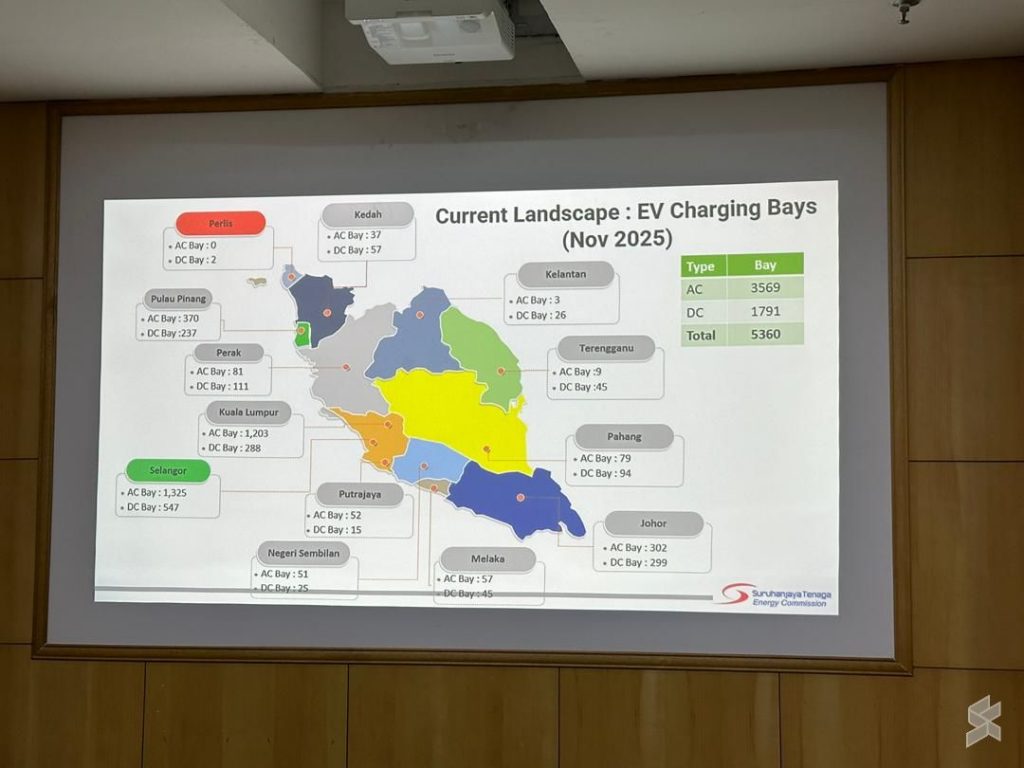

According to the Energy Commission’s (ST) latest data as of November 2025, Malaysia has 5,360 EV charge points, which is only about half of the national target of 10,000 EV charge points by the end of 2025.

By comparison, Singapore already has around 25,000 EV charge points, with roughly half accessible to the public. This translates to approximately one charge point for every three EVs in the island republic. In Malaysia, the current ratio is one charge point for 15 EVs based on JPJ and ST figures.

Despite missing the target, Malaysia’s EV charging infrastructure rollout has been growing at a healthy pace. Unlike some other countries, Malaysia’s EV charging deployment is largely driven by the private sector, without direct government subsidies or incentives specifically aimed at expanding charging infrastructure.

Charge point operators such as Gentari, ChargEV, TNB Electron and DC Handal have been steadily increasing the number of public EV charge points, making most interstate routes increasingly viable for EV drivers.

Compared to two years ago, it is now possible to travel in a 300km range EV from Kuala Lumpur to Kota Bharu, Penang to Kota Bharu, as well as from Kuching to Miri thanks to the latest EV charger deployments. DC fast chargers are also no longer limited to major cities, with growing deployment in smaller secondary towns as well.

Building EV-ready highways: What’s holding Malaysia back

EV charging hubs along interstate and major highway routes are critical infrastructure if Malaysia wants to make long-distance EV travel practical and to eliminate range anxiety.

Chargers at regular intervals on highways allow drivers to top up their EVs while taking a break, much like rest areas and petrol stations do for conventional cars. This is not just about convenience, but confidence in the network.

However, charge point operators continue to face significant challenges in rolling out proper highway charging hubs. Securing land and long-term leases at R&R sites often requires negotiations with multiple concessionaires and operators, which can be slow and commercially complex.

High upfront costs, lengthy approval processes and the need for major electrical capacity upgrades further complicate deployment. If a CPO requires more power at a location to deliver high-powered DC charging, it would have to invest in a substation, even though the substation itself is not exclusive to the CPO.

These constraints explain why many EV chargers at highway R&R sites today are still limited to two or three bays. While sufficient on normal days, such setups would struggle during peak festive travel when demand spikes sharply.

To work around these limitations, several CPOs have turned to building charging points just off the highway to complement existing R&R chargers.

These sites offer less constraints and easier access to power but they require users to exit the highway. Such examples of off-highway chargers include Gentari EV Charging Hub Bandar Baru Ayer Hitam, ChargEV’s charging hub at Tangkak Pitstop, TNB Electron Politeknik Sultan Azlan Shah in Behrang, Gentari Petronas Ayer Hitam 3, and Charge+ Amverton Heritage Resort.

These off-highway hubs have helped make interstate EV travel far more viable than it was just a few years ago. However, they remain a workaround rather than a substitute for fully EV-ready highways.

For broader and more resilient deployment, Malaysia needs a clear mandate from the highway regulator, LLM, to designate EV-friendly corridors by ensuring minimum number of charge points at R&R sites, and streamline land access and power supply requirements.

This means integrating EV charging into highway planning from the start, ensuring grid capacity is provisioned ahead of demand, and coordinating closely with utilities providers to prioritise power upgrades at strategic routes.

Malaysia could also take a leaf from its own fibre broadband rollout. During the High Speed Broadband (HSBB) initiative, the government recognised that nationwide connectivity would not happen if deployment was left purely to market demand.

Through a public–private partnership with Telekom Malaysia, fibre infrastructure was rolled out not just where it was immediately profitable, but where it was strategically necessary. Government funding, long-term planning and clear targets helped de-risk investment and allowed infrastructure to be built ahead of demand.

Imagine having large-scale EV charging hubs located every 100km along interstate highways, each with at least 20 DC charge points and megawatt-level capacity.

For greater redundancy and accessibility, each charging hub should host at least two CPOs, with all charge points offering open payment via credit and debit cards for greater convenience.

These hubs must also include provisions for commercial EV charging, as more electric buses, lorries and prime movers are expected to use Malaysia’s major highways in the future.

Only with this level of coordinated planning will Malaysia’s highways truly be ready for mass EV adoption.