Malaysians are a hungry bunch. For Internet shows, I mean (though we quite like food too #Understatement). And our appetite has drawn some unexpected attention from industry bigwigs. Just look at Netflix’s recent announcement of the RM17-per-month mobile plan.

The surprise isn’t on the plan itself – many people and their K-drama-loving mums have already known about it since last year – but that Netflix chose to launch it in Malaysia. This makes us the second country in the world (after India) and the first country in Southeast Asia to get the cheaper plan.

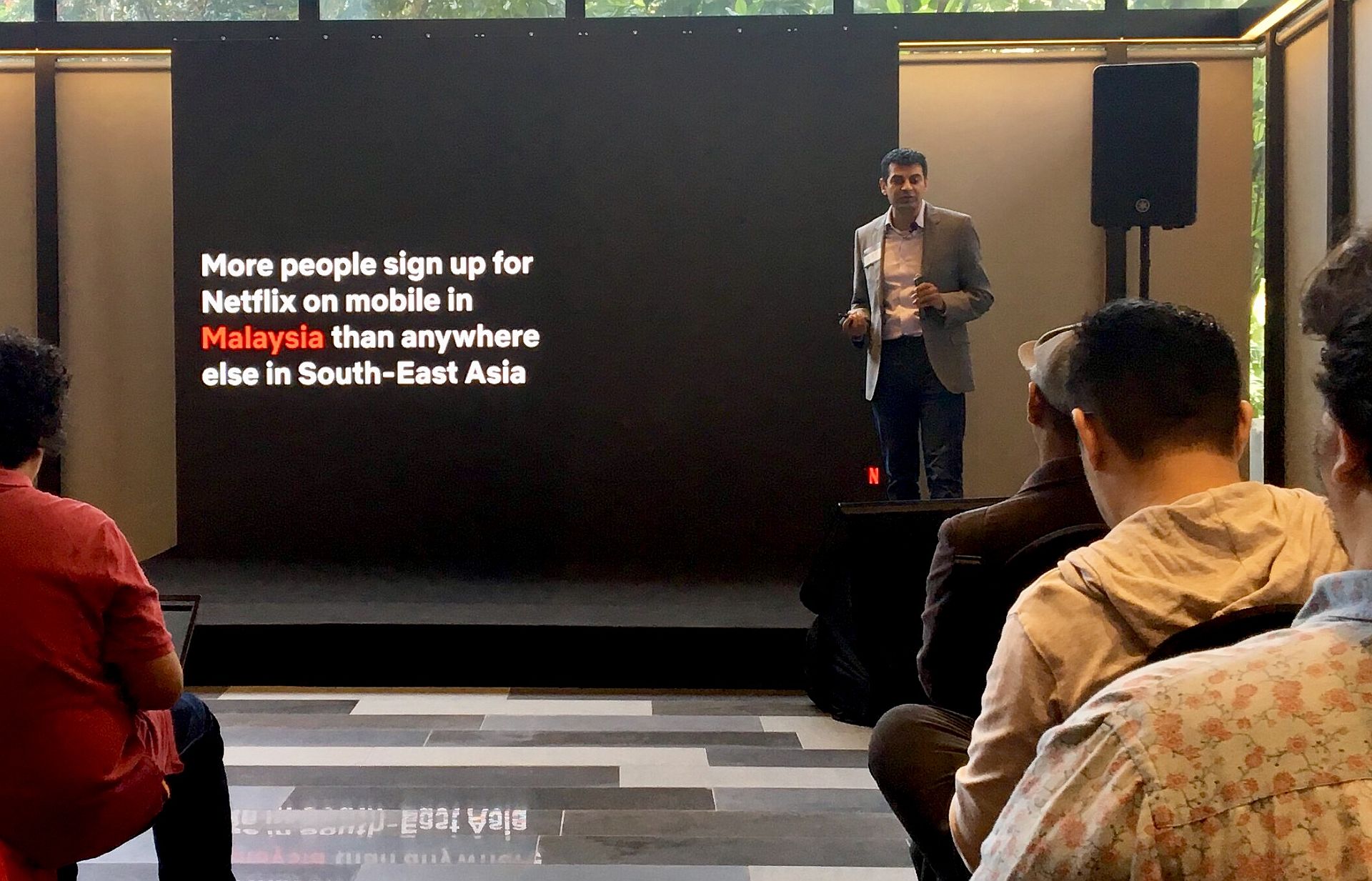

Malaysians devour two times more Netflix on mobile compared to the rest of the world, according to Ajay Arora, the platform’s Director of Product Innovation, who flew down from sunny California to sunny Damansara Perdana to officially unveil the new mobile plan. He also revealed that more people sign up for Netflix on mobile in Malaysia than anywhere else in Southeast Asia.

This jives with recent reports on Malaysians’ mania for mobile video. Maxis chief technology officer Morten Bangsgaard, for example, told Malay Mail in October that the telco’s MaxisONE Prime customers consume around 15GB to 25GB monthly, with over 80 per cent of their data usage being spent on video streaming, mostly on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram.

With great demand comes great competition

With great demand comes great competition. Streaming video platforms – from homegrown iflix to Hong-Kong-backed Viu – are beefing up their content buffet to satiate audiences. Reinvention is also necessary amidst the streaming wars.

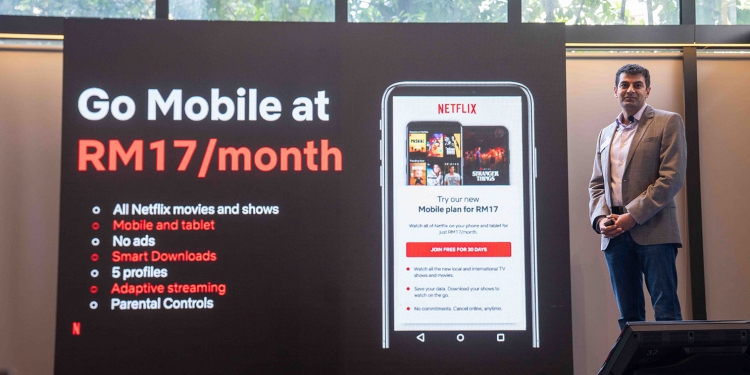

For Netflix, it means rolling out an RM17-per-month, mobile-only plan. Pricing has been its Achilles heel. Its cheapest plan used to be RM33 per month, which was two to three times higher than what many other platforms in the region charge (if they charge at all – Viu and iflix has a free tier which allows users to watch with ads).

The question is whether the lowered price of streaming subscription benefits users. Watching shows online, especially bingeing television series, demands heavy data usage, which means a higher telco bill.

It appears that Netflix had thought about this. In an interview with DeconRecon, Ajay explained that the platform did not want users to end up paying for more data usage, which would diminish the cost-saving appeal of the cheaper mobile plan.

“Look, the plan is one thing, but what happens when the data cost doubles the price of the plan? That would not be a good user experience either,” he said.

Lowering the mobile data demand

Thus, Netflix had begun lowering the data demand of its shows. Ajay explains that, back in 2011, videos used to be encoded in a one-size-fits-all manner – all titles come in the standard definition of 1,000kbps. Then, Netflix started rolling out ‘per-title encoding’, which means each title can vary between demanding 640kbps to 1,000kbps (the more cinematic quality required, such as for big action scenes, the higher the data demand).

Now, he says, Netflix is busting out ‘per-shot encoding’, which means a dynamic data demand “as low as 250kbps to many Mbps”.

And because I had as many question marks over my head as you probably do reading this, I emailed Netflix’s rep to get some explanations.

“Basically, per-shot encoding means that we take the whole video and break it up into shots (each shot is about four-seconds long). Each of these shots gets encoded separately. By using this technique, we are able to put together all the shots and ensure that we give the best shot for each bandwidth level,” said the written reply. “Certain scenes have higher data demand, but others have lower data demand, so when you can combine those, overall [this entails] less data required.”

In plain English – 1GB of data can play 1.5 hours of Netflix content in 2011. Today, it’s 6.5 hours. Essentially, one can watch the whole season of Stranger Things on just over 1GB of data.

Complementing the cheaper plan is an improved user experience on lower-end smartphones – via Netflix’s adaptive streaming technology. ‘Adaptive’, because the Netflix app can detect phone capabilities and adapt the user experience accordingly. For example, those using entry-level smartphones would not have auto-playing trailers on the home screen and would see smaller icons, compared to those using smartphones with higher processing power.

“We didn’t want a Netflix Lite app. So we made the app intelligent,” said Ajay.

For now, however, Netflix told DeconRecon that the majority of its users in Malaysia use high-end smartphones.

He also addressed worries on whether there are user privacy risks with the new adaptive video streaming technology. The app can only ‘read’ the phone’s performance-related information like memory and processing power – Ajay explained that Netflix does not have permission to access other private data in the device (though according to reports, it may already have).

Other than adapting to device types, the app is also able to tailor streaming quality and data demand to network strength fluctuations via machine learning.

This basically means that when you are commuting and start streaming, say, Kingdom or Carole and Tuesday, the video should theoretically keep playing – at a lower quality – when your network signal weakens or temporarily drops at certain places. Then, when the Internet goes back to normal, your video will go back to playing at your selected quality.

“We want playback to start instantly, stream at great quality, and never stop unexpectedly,” as the website puts it.

Is this the end to buffering? We’ll have to watch and find out. — Reported by LM Foong/DeconRecon